Hampsfell Hospice (or 'Hospice of Hampsfield Fell')

|

The Hospice was built in 1834 (or 1846 – depending on the source) by the Reverend Thomas Remington, Vicar of Cartmel from 1835-1854[1]. He built it as a shelter for wanderers over the fell, and as a thank offering for all the beauty he had seen there on his daily climb up to the summit from his home at Aynsome in the Cartmel Valley.

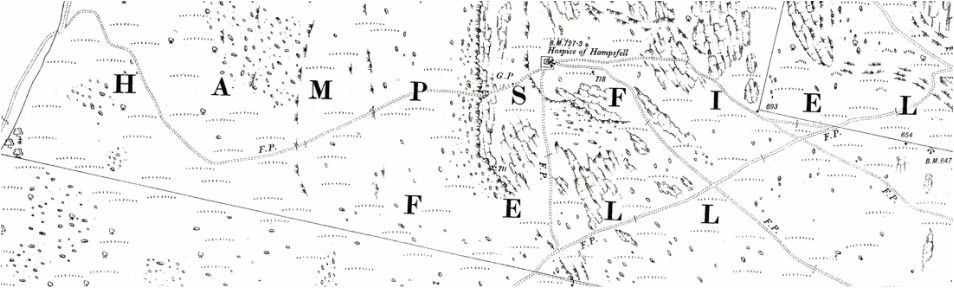

It is on the summit of Hampsfell (more properly – Hampsfield Fell), and the benchmark on top of the Hospice (a small metal stud) is at 727.3 feet above sea level.

It is on the summit of Hampsfell (more properly – Hampsfield Fell), and the benchmark on top of the Hospice (a small metal stud) is at 727.3 feet above sea level.

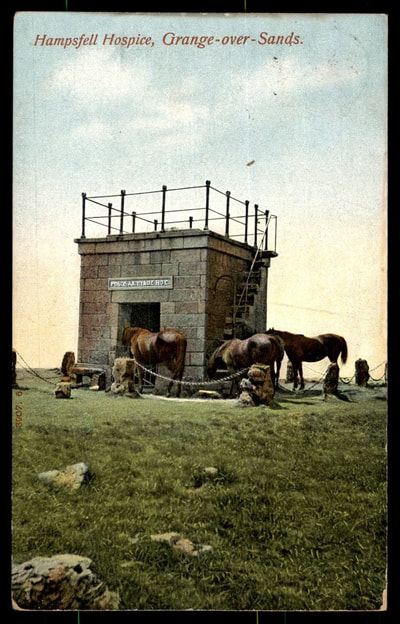

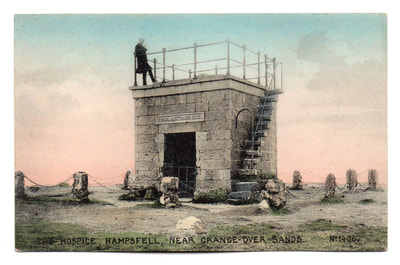

The iron railing, and rail up the steps were added later by a relative of Remington, sometime between 1866 and 1892. Older guidebooks and newspaper descriptions refer to the steps needing a rail - it must have been quite tricky climbing them before this was added.

It is a stout four sided shelter, about 20’ high, with stone bench seats and a fire place inside. And a small The chimney for the fire is an odd sort of drain pipe across the corner – presumably to provide draw without going straight up onto the roof. Because on the roof is where people gather to see a quite stunning view – once they’ve negotiated some very steep and narrow steps that have just a thin iron rail for support.

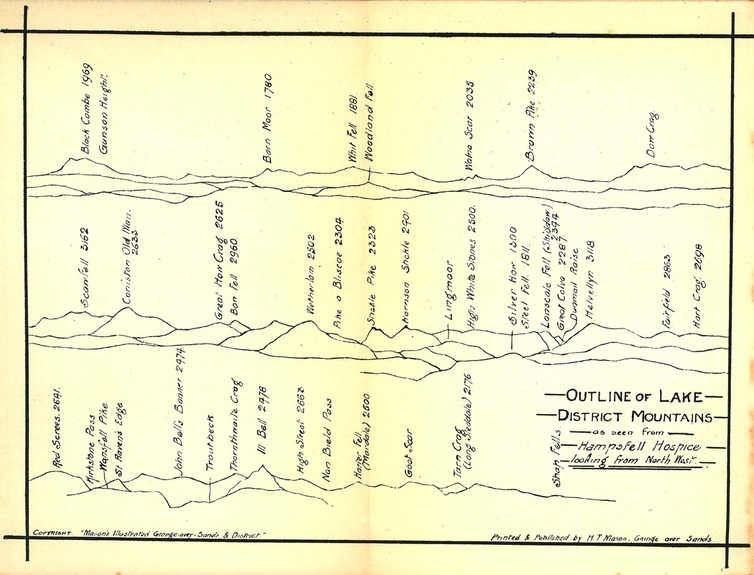

It’s one of the best ‘summit’ views that you can get without a great deal of effort, giving a 360 degree panorama – from Blackpool Tower to Helvellyn and beyond. Edwin Waugh described the views as "indeed glorious, both in variety of character and extent of range. Fertile, peace-breathing valleys; old castles and churches, and quaint hamlets and towns,—eloquent relics of past history; lonely glens, rich parks, and forest steeps; picturesque homesteads, in pleasant nooks of shelter; beautiful estuaries; the fresh blue bay; bleak brown moorlands; wild craggy fells; and storm-worn mountains, each different in height and form, the grand old guardians of the magnificent scene."

What’s more there is a very unusual ‘compass’ on the top. It’s a wooden pointer that revolves on a plinth. You line the pointer up with a hill, read the compass bearing on the iron hoop, and then look at the list on the board to see which peak corresponds with your bearing. Markers like this are generally called ‘toposcopes’, although this really means the sort of thing on Orrest Head where you have something with lines pointing at places, or a topographical picture of the peaks. The pointer is probably more technically known as an ‘alidade’.

This wasn't an original part of the Hospice, Victorian photographs show the Hospice without it. Some sources say that it was a labour of love made by a retired railwayman,

a Mr. Garstang (see postcards later).

It is a stout four sided shelter, about 20’ high, with stone bench seats and a fire place inside. And a small The chimney for the fire is an odd sort of drain pipe across the corner – presumably to provide draw without going straight up onto the roof. Because on the roof is where people gather to see a quite stunning view – once they’ve negotiated some very steep and narrow steps that have just a thin iron rail for support.

It’s one of the best ‘summit’ views that you can get without a great deal of effort, giving a 360 degree panorama – from Blackpool Tower to Helvellyn and beyond. Edwin Waugh described the views as "indeed glorious, both in variety of character and extent of range. Fertile, peace-breathing valleys; old castles and churches, and quaint hamlets and towns,—eloquent relics of past history; lonely glens, rich parks, and forest steeps; picturesque homesteads, in pleasant nooks of shelter; beautiful estuaries; the fresh blue bay; bleak brown moorlands; wild craggy fells; and storm-worn mountains, each different in height and form, the grand old guardians of the magnificent scene."

What’s more there is a very unusual ‘compass’ on the top. It’s a wooden pointer that revolves on a plinth. You line the pointer up with a hill, read the compass bearing on the iron hoop, and then look at the list on the board to see which peak corresponds with your bearing. Markers like this are generally called ‘toposcopes’, although this really means the sort of thing on Orrest Head where you have something with lines pointing at places, or a topographical picture of the peaks. The pointer is probably more technically known as an ‘alidade’.

This wasn't an original part of the Hospice, Victorian photographs show the Hospice without it. Some sources say that it was a labour of love made by a retired railwayman,

a Mr. Garstang (see postcards later).

The peaks that can be seen are shown more traditionally in the 'Pocket Guide' from 1917. Interestingly, the old books also say that you could burn ling (heather) and ferns in the fireplace. I'm not sure how many decades it is since there was heather on the fell - but there isn't any now.

Outside there are some large limestone block seats where you can sit in the sun, out of the wind, and listen to the skylarks (repaired in 2018). The small chains set in limestone uprights set the Hospice apart from the rest of the land – and give an almost proprietorial feel to the place when you’re inside them.

The whole building is listed Grade II.

Above the iron gated doorway is a frieze with Greek lettering RODODAKTYLOS EOS" (Rosy-fingered Dawn; a quotation from Homer) – probably chosen because it faces due east into the sunrise at the equinox, as the photos show. And therefore glows in the dawn. Homer often uses this phrase when referring to Eos, the Titanic goddess of the dawn. Wainwright, in his usual dry way, said “Outside, over the doorway, is an inscription that will be Greek to most visitors’.

Remington apparently walked up to the top of Hampsfield Fell at 6am every morning - so would generally have faced the sunrise.

There are small windows in three of the walls – which used to be open with shutters, but have been filled in with Perspex sometime in the last 30 years.

Conservation statements have been published and make interesting reading, especially the second one:

www.recordingmorecambebay.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/H2H_0072.pdf

https://www.recordingmorecambebay.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/H2H_0073.pdf

On the inside walls are lettered boards with a notice about the Hospice and three poems (1846), some of which were replaced by the National Park Authority in about 1990.

There are plenty of walks and guides of how to get to the Hospice - such as here. The easiest is probably to park near the golf course at the bottom of Spring Bank Road. But from town, the way is up Hampsfell Road. From the station, the paths through Eggerslack Wood are excellent up on to the fell.

The Hospice stands within ‘Longlands Allotment’, which was created out of the larger Hampsfield Fell during the Enclosure Process of 1796-1803. You can’t avoid passing over or through at least one wall on your way to the Hospice, and these were nearly all built at that time. Don’t miss the lovely stone stile to the south of the Hospice, it’s a gem of its kind – it’s just off the main walked route, but is actually on the public footpath.

Other things to see when you’re up there:

The Hospice stands within ‘Longlands Allotment’, which was created out of the larger Hampsfield Fell during the Enclosure Process of 1796-1803. You can’t avoid passing over or through at least one wall on your way to the Hospice, and these were nearly all built at that time. Don’t miss the lovely stone stile to the south of the Hospice, it’s a gem of its kind – it’s just off the main walked route, but is actually on the public footpath.

Other things to see when you’re up there:

- The view...

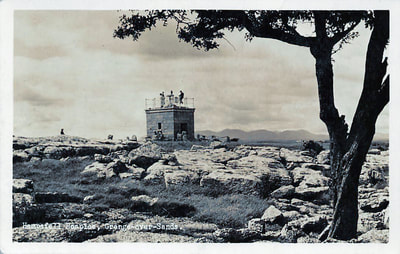

- Plenty of limestone pavement;

- Ancient clearance cairns (or possibly a burial cairn according to some sources);

- The windswept Hawthorns;

- Sloes around Cockle Well if you’re lucky.

The Hospice is great all day long from Sunrise to Sunset, as these photos show. If you can get there for sunrise, I highly recommend it - as walking back down gives some fantastic views of the sun rising over Morecambe Bay and Arnside Knott.

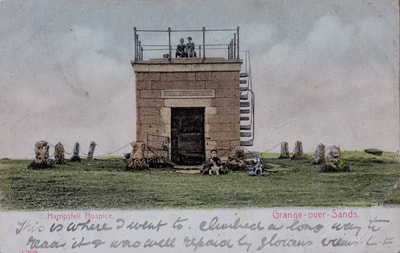

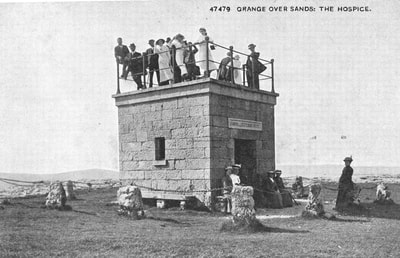

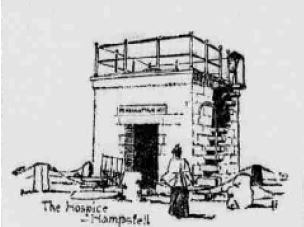

The following are postcards of the Hospice. All except the final one (1969 postmark) are late Victorian or Edwardian - the tinted ones were also produced in black & white. You can see that the direction finder on the top was not present. It looks as though the gate has been replaced at some time, but otherwise it looks much the same.

The Annals of Cartmel has a fascinating story about the 'Hampsfield Fell Feite'. This describes how panic was spread in the people of Cartmel in November 1745. There was great alarm about the rebel army advancing, possibly towards Cartmel. A great number of men, women and boys assembled at the summit of Hamspfield Fell armed with every manner of weapon possible - pitchforks, scythes, knives, sticks and stones. One man (Barwick) was dispatched on a horse over the sands and was to ride back to give notice when the army was on its way. After six hours or so, a rider was spotted coming fast over the sands, and terror shot through the crowd, who all ran round and round not knowing quite what to do. Then one or two left the top of the fell, which suddenly left to a mass of people running pell-mell down the hill back to Cartmel where they barricaded themselves in their houses. When Barwick finally arrived back in Cartmel - with 'nothing to report' couldn't find anyone to give the news to. The Annals report is far longer and more descriptive - and worth a read.

[1] The Reverand Thomas Remington was born in 1801 or 1802 at Melling, he studied at Emmanuel and Trinity, Cambridge (MA). He was ordained in 1826, and became curate of Buckden, Huntingdon. He then inherited Aynsome from his uncle. In 1835 the Duke of Devonshire presented him the Vicarage of Cartmel, where he remained until his death in 1855 (he caught smallpox on a visit to London and dies at his monther’s house in Melling). He obtained permission from the Bishop of Chester to live at Aynsome rather than the Vicarage – and was looked after there by his unmarried sister, Isabel.

Some sources say that George Remington built the Hospice, possibly because the ‘Notice’ inside has his name on it. However, George was a relative. He was the son of Henry, an Ulverston Solicitor, and was himself an articled clerk, his parents moved to Aynsom after Thomas’ death. It is possible that George erected the railings on the Hospice, and also possible that he wrote the poems on the inside boards.